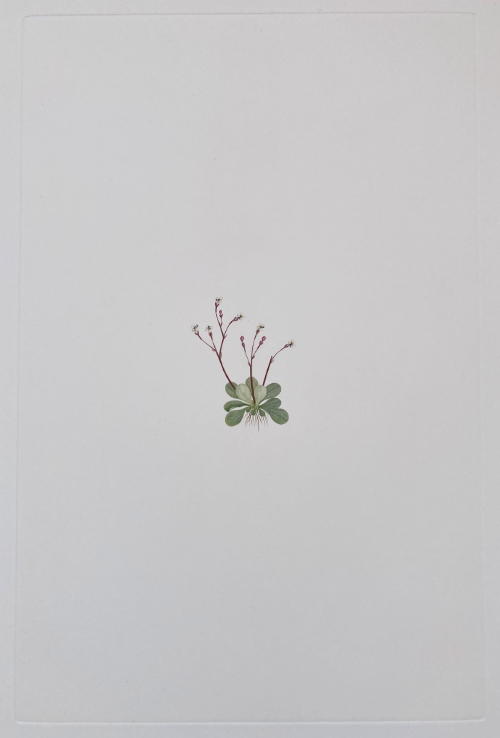

SYDNEY PARKINSON and FREDERICK POLYDORE NODDER (artists). ‘Plate 173. Stylidium Rotundifolium, R. Brown, Lobeliastrum latifolium (Stylidiaceae)’. London: Alecto Historical Editions in association with the British Museum (Natural History), 1982.

Engraving by Daniel MacKenzie, printed à la poupée by Alecto Historical Editions. Platemark circa 457 x 305mm, printed on acid-free Somerset mould-made 300gsm paper manufactured by the Inveresk Paper Company. The sheet is watermarked ‘AHE’, measures 724 x 556mm, and bears blind embossed stamps incorporating the publishers’ and printer’s chops, the copyright symbol, and date of publication; the initials of the individual printer, the plate number, and the edition number are recorded in pencil. The engraving is protected by a bifolium of acid-free Somerset mould-made 300gsm paper, cut to form a window mount on which is recorded the modern and Banksian name of the plant, the location and date of its collection and the names of the artists and engraver.

STYLIDIUM ROTUNDIFOLIUM, R. BROWN, LOBELIASTRUM LATIFOLIUM

(STYLIDIACEAE)

Species collected at Endeavour River, Australia

17 June – 4 August 1770

Limited to 116 impressions, this no. 2 of 3 for exhibition and numbered ‘EP 2/3’

His Majesty’s Bark Endeavour had been sent to the Pacific with the purpose of observing the 1769 transit of Venus across the sun, launching from Plymouth in 1768, and approaching New Zealand via Brazil and the Society Islands in the course of the following nine months. But it was Cook’s decision to proceed via the east coast of the continent then known as New Holland in 1770 that would be the first step towards the British settlement of Australia. Joseph Banks’ botanical discoveries – some 1,300 previously unknown botanical species – revolutionised European understanding of natural history.

The Stylidium Rotundifolium is one of seven Stylidium plants discovered by Banks and Solander (out of ca. 300 known to belong to the species today). It is an annual plant found in northern Australia, growing up to 18cm tall, and flowering from April to October. Like the Dendrobium Canaliculatum, the Stylidium Rotundifolium would not be described scientifically until it appeared in Robert Brown’s Prodromus Florae Novae Hollandiae et Insulae Van Diemen (London, 1810, vol. 1, p. 571).

‘By 28 July the excitement to find new plants had vanished; there seemed to be none left to find. “Botanizing with no kind of success”, Banks wrote in his journal, “The Plants were now intirely completed and nothing new to be found, so that sailing is all we wish for if the wind would but allow us”. On 3 August the Endeavour set sail again’ (Stearn, ‘A Royal Society Appointment’, p. 114).

The history of the Florilegium

The seeds for Joseph Banks’ Florilegium had been planted with his earliest expedition: on his return to London from Labrador and Newfoundland, Banks had commissioned the young Scottish natural history artist Sydney Parkinson to draw some of the natural history specimens from the expedition on HMS Niger. On the Endeavour, Banks took both Solander and Parkinson (who sadly died at sea in January 1771) with him as members of his scientific party. On his return to England Banks planned an account of the expedition’s botanical discoveries, and employed a team of engravers to produce copper plates of Parkinson’s drawings. 743 plates were engraved under Banks’ supervision by eighteen engravers over a period of thirteen years, at a cost of more than £7,000. Manuscript descriptions of the specimens were prepared by Daniel Solander, but (apart from some small groups of proof plates) the long-anticipated work remained unpublished at Banks’ death in 1820, nearly fifty years after he had returned from the Endeavour expedition.

On Banks’ death, the engraved copper plates were bequeathed to the British Museum, where they remained in storage until 1900-1905, when monochrome lithographic plates of the Australian flora were made after the original plates (British Museum, Illustrations of Australian Plants, reproducing 320 of the 743 images). The 1973 limited edition (100 copies) of Captain Cook’s Florilegium, edited by Wilfrid Blunt and W.T. Stearn included a small number of engravings printed from the original copper plates in black ink only.

It was not until 1979, following successful trial printings of the plates in colour, that Alecto Historical Editions and The British Museum (Natural History) agreed to jointly publish the full set of 738 plates (five of the original 743 had been stolen), printed in colour à la poupée (i.e. by applying the colour to the plate with a cotton ball, and then adding further colour if necessary with a brush). Only 100 sets of Banks’ Florilegium, which appeared between 1980 and 1990, were printed for sale (of which all were subscribed), together with sixteen further sets, comprising three printers’ proof sets (of which number 1 is at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew); three sets printed for exhibition purposes; and ten hors commerce sets (120 plates from set no. VII were sold by Sotheby’s, London in 1988 to benefit the Banks Alecto Endeavour Fellowship, and sets IX and X went to The British Museum, Natural History).

The reception was enthusiastic: The Book Collector (vol. XXXVIII, 1989) considered the Alecto edition ‘a triumph on many scores: a triumph of imagination, to conceive such an enterprise; a triumph of aesthetic sensibility, to realize that plates originally intended to be printed in black could be rendered in colour with such magical beauty, yet true to nature; a triumph of technical skill, to restore the tarnished plates and print them with unerring precision, maintaining the same high standard from first to last . . .; a triumph, above all of tenacity to bring such a colossal enterprise . . . to a final successful conclusion’.

£125 inc. VAT

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

Our Terms & Conditions apply.