A JUVENILE NOVEL GIVEN TO THE YOUNG RUPERT BROOKE BY HIS BROTHER RICHARD,

AND LATER OWNED BY THEIR YOUNGER BROTHER ALFRED

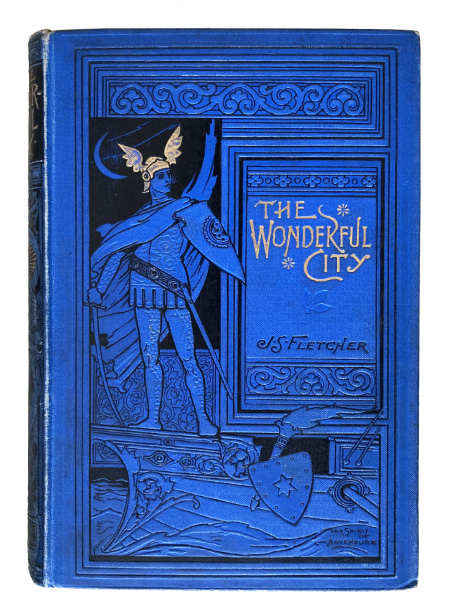

BROOKE, Rupert Chawner – Joseph Smith FLETCHER. The Wonderful City. London, Edinburgh, and New York: T. Nelson and Sons, 1894.

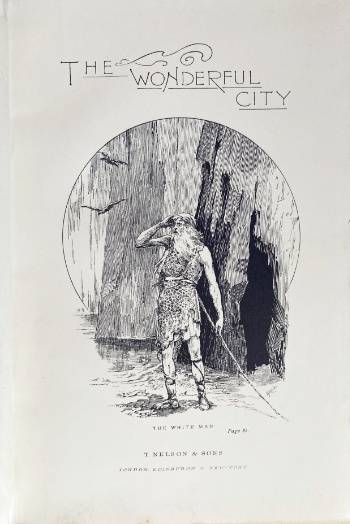

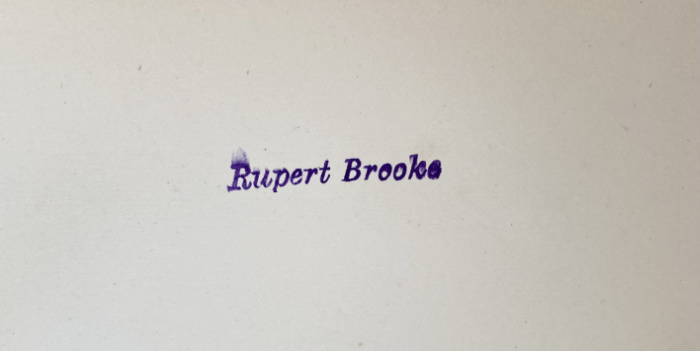

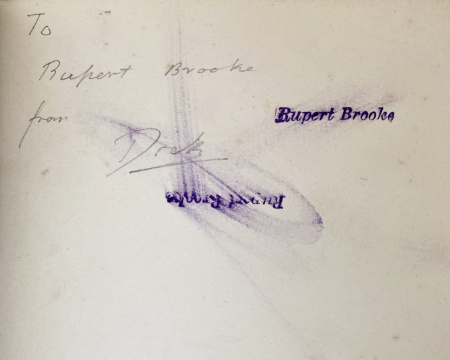

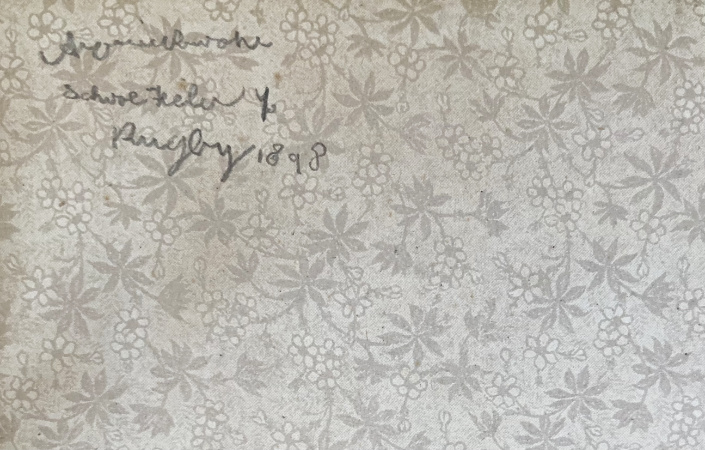

Octavo (180 x 118mm), pp. [i]-vii (blank l., title, verso blank, contents), [1 (blank)], [9]-185, [1 (blank)], [6 (publisher’s catalogue)]. Frontispiece after A. Rhind, additional title with vignette after Rhind, retaining tissue guard, and one map in the text. (A few light spots and marks.) Original blue cloth, upper board and spine blocked with design in gilt and black, lower board blocked in blind with publisher’s device, patterned floral endpapers. (Spine slightly faded, some very light marking, extremities slightly rubbed and bumped.) Provenance: Richard England (‘Dick’) Brooke (1881-1907; gift to his younger brother:) – Rupert Brooke (1887-1915, pencilled presentation inscription ‘To Rupert Brooke from Dick’ on front flyleaf; ‘Rupert Brooke’ inkstamps on front flyleaf and verso of frontispiece; presumably given to his younger brother:) – William Alfred Cotterill Brooke, School Field, Rugby School, 1898 (1890-1915, pencilled ownership inscription on front free endpaper ‘Alfred Brooke School Field [-] Rugby 1898’) – [?Sir Geoffrey Langdon Keynes FRCP, FRCS, FRCOG, FBA (1887-1982, Rupert Brooke’s friend, bibliographer, editor, and literary executor; by descent to his son:)] – Stephen John Keynes OBE, FLS (1927-2017).

First edition. The Wonderful City was one of the earliest novels by the British novelist, poet and journalist J.S. Fletcher (1863-1935), and was published shortly before the author relinquished his employment as a journalist to write full time. The work was intended for a juvenile audience, and is described by Bleiler as a ‘[l]ost race novel [set] in the area where Arizona, Utah, New Mexico, and Colorado meet’, which is a ‘weak imitation of H. Rider Haggard’. This copy (which is bound in a blue cloth believed to be the earliest state of the bindings) is from the library of the poet Rupert Brooke, who was the second of the three sons of the schoolmaster William Parker Brooke (1850-1910) and his wife Mary Ruth Brooke (d. 1931). William Brooke had been appointed a classics master at Rugby School in 1880, and he was subsequently appointed housemaster of the ‘School Field’ boarding house in 1891. The Brooke family moved into School Field, and this volume was presumably given to Rupert Brooke by his brother Richard (known within the family as ‘Dick’) in the years after its publication in 1894, when Rupert Brooke was seven. In turn, Rupert Brooke appears to have passed it on to his younger brother Alfred Brooke, whose ownership inscription dated 1898 appears on the front free endpaper.

This volume was later in the library of the noted bibliophile and collector Stephen Keynes, and it is believed that he inherited it from his father Sir Geoffrey Keynes, who had been a friend of Rupert Brooke’s since their schooldays. Both boys had entered Rugby School in September 1901 at the age of fourteen (Brooke, like both of his brothers, attended Hillbrow preparatory school in Rugby before entering Rugby School), and Keynes spent his first term at one of the smaller boarding-houses, before moving to School Field in January 1902. At School Field Keynes soon ‘began to fall under the spell of Rupert Brooke, son of the housemaster. […] Rupert, although a few months younger than I, was very much wiser and more clever, and he soon became the friend to whom I turned with complete confidence and admiration’, until, when he was at Rugby, Keynes ‘was now seeing more of Rupert Brook than of anyone else’ (G.L. Keynes, The Gates of Memory (Oxford, 1981), pp. 36-37). The friendship continued to develop as the two boys entered the upper years of the school, and Brooke ‘was writing more poetry and getting some of it printed in school magazines. Impressed by this sign of genius, I began collecting and keeping everything he produced, the natural beginning of my bibliographical instincts with, I felt sure, a worthy object’ (op. cit., p. 40). Towards the end of the Michaelmas term of 1905 Brooke and Keynes travelled to Cambridge to sit the University entrance examination, which resulted in a scholarship in classics at King’s College for Brooke and an exhibition at Pembroke College for Keynes.

At Cambridge Geoffrey Keynes followed Rupert Brooke’s lead in joining the Fabian Society, and the two friends were among the earliest members of the Marlowe Dramatic Society. After graduating in 1909 Brooke moved to Grantchester, where he became the centre of a group dubbed the ‘Neo-Pagans’ by Virginia Woolf, which included Keynes, his future brother- and sister-in-law Jacques Raverat and Gwen Darwin, and his friend and future publisher, David Garnett. In a vivid sketch of the Neo-Pagans at this time, Woolf wrote that Brooke ‘was living at Grantchester; his feet were permanently bare; he disdained all tobacco and butcher’s meat; and he lived all day, and perhaps slept all night, in the open air’ and ‘[u]nder his influence the country near Cambridge was full of young men and women walking barefoot, sharing his passion for bathing and fish diet, disdaining book learning, and proclaiming that there was something deep and wonderful in the man who brought the milk and in the woman who watched the cows’ (quoted in H. Lee, Virginia Woolf(London, 1996), p. 293). Keynes spent a further year at Cambridge studying medicine, before moving to London in 1910 to continue his medical studies at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, and in the following years the two men only met occasionally, before Brooke embarked on a year of overseas travel in May 1913.

On the outbreak of World War I in August 1914, Keynes left his position as a senior house surgeon at St Bartholomew’s and was commissioned into the Royal Army Medical Corps with the rank of lieutenant. Keynes joined his unit at Woolwich on 16 August 1914, and ‘[o]n 18 August I chanced to meet Rupert Brooke near my rooms in Bloomsbury. He gazed at my uniform with envy and almost with despair. Like many other young men, he was having the greatest difficulty in deciding in what capacity he ought to serve’ (The Gates of Memory, pp. 124-125). Nonetheless, Brooke’s ‘difficulties were finally resolved through the good offices of Eddie Marsh and Winston Churchill. By the middle of September he had obtained a commission in the Naval Division (R.N.V.R.)’ (G.L. Keynes (ed.), The Letters of Rupert Brooke (London, 1968), p. [557]), and in October 1914 Brooke took part in the Antwerp Expedition, before returning with his division to England, where he composed his five ‘War Sonnets’.

On 22 August 1914, a few days after that last meeting, Keynes’s unit left Woolwich for France, where he was assigned to a field hospital based in a requisitioned hotel at Versailles. Keynes remained at the hospital for four months ‘steadily gaining experience of how to deal with the wounds of modern warfare’ (The Gates of Memory, p. 128), and in February 1915 – the month that Brooke’s division sailed for Gallipoli – Keynes was transferred to an ambulance train, which was based at Boulogne. While serving on the train, ‘[o]n 27 April [1915], I had news of the death of Rupert Brooke three days earlier in the Aegean, and I became more aware of the fate of which was to kill the majority of the friends of my generation at Rugby and Cambridge’ (op. cit., p. 130).

Rupert Brooke’s older brother Dick had died of pneumonia in 1907 as a young man, their father had died in 1910, and Alfred, the surviving brother, was killed in action in France on 14 June 1915, at the age of 24, which left their widowed mother the sole survivor of the family. After Rupert Brooke’s death, Keynes ‘continued to feel a special obligation to his mother, who until her death in 1931 treated me almost as a son’ (op. cit., p. 165), and he was appointed one of the four Literary Trustees of the Estate in Mary Brooke’s will, in which capacity Keynes took custody of a large portion of Brooke’s archive, which had been in the possession of Sir Edward Marsh. Following the publication of his edition of The Poetical Works of Rupert Brooke in 1946 and his Bibliography of Rupert Brooke in 1954, Keynes would go on to edit Rupert Brooke’s letters, which were used extensively by Christopher Hassall for his book Rupert Brooke: A Biography(1964) and then published as The Letters of Rupert Brooke. Chosen and Edited by Geoffrey Keynes in 1968.

Rupert Brooke had set out instructions to be carried out in the event of his death in a letter to his friend Dudley Ward dated 17 March 1915, writing that Ward would ‘have to give the Ranee [i.e. Mary Brooke] a hand about me: because she knows so little about great parts of my life. There are figures [who] might want books or something of mine. Noel [Olivier] and her sisters, Justin [Brooke], Geoffrey [Keynes], Hugh Russell-Smith’ (The Letters of Rupert Brooke, p. 672). Keynes recorded that he received Brooke’s copies of the Greek dictionary of Liddell and Scott and the Latin dictionary of Lewis and Short (which both boys had used when studying classics together at Rugby), and wrote that ‘[I] have used them constantly ever since, stirring memories each time I have pulled one from the shelf’ (The Gates of Memory, p. 38). It seems possible that Keynes also chose this copy of Fletcher’s The Wonderful City as a relic of his friend’s earlier schooldays and home life; alternatively, he may have received it at a later time from Mary Brooke’s library (for other books from Brooke’s library gifted by Mary Brooke after her son’s death, see J. Schroder, Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts by Rupert Brooke, Edward Marsh & Christopher Hassall (Cambridge, 1970), nos 170 and 171).

Although books from Rupert Brooke’s library are periodically offered on the market, they are not common and this example is, we believe, of greater rarity than most, since it is the only volume we are aware of that passed through the hands of all three brothers during their childhood living at Rugby’s School Field house. Since Brooke was given the volume between 1894 (when it was published) and 1898 (when it passed to his younger brother), it is also one of the few volumes which Rupert Brooke is known to have owned as a boy before he became a student at Rugby School in 1901. We have not been able to trace any other books he owned at this time on the market, and the online catalogue of King’s College, Cambridge only identifies three volumes which were certainly in Brooke’s possession at this period: The Book of Common Prayer, inscribed ‘Rupert C. Brooke. School Field, Rugby. May 1893’; F.W. Farrar’s Eric or, Little by Little: A Tale of Roslyn School, inscribed ‘Rupert Brooke with best wishes from E.R. Banks, Xmas 1898’; and Shakespeare Birthday Book, inscribed ‘Rupert C. Brooke from M.A.T., Xmas 1898’ (Archive Centre, King’s College, Cambridge, GBR/0272/RCB/Pr/72, GBR/0272/RCB/Pr/81, and GBR/0272/RCB/Pr/100 respectively; an undated Bible inscribed ‘Rupert C. Brooke. School Field Rugby’ (GBR/0272/RCB/Pr/67), a copy of Holy Communion (1901) inscribed ‘To Rupert Brooke with every good wish for his confirmation from Albert Baillie Rector’ (GBR/0272/RCB/Pr/89), and a few other books with pre-1901 imprints but undated marks of ownership are also listed in the catalogue). It is also notable as the only volume from Brooke’s library that we have been able to trace which has been marked with an inkstamp bearing his name (these books usually bear his ownership signature or inscription, Brooke’s own bookplate, a posthumous bookplate produced by his executors, or a combination of these), suggesting that he only used the inkstamp briefly to mark a small number of his books.

E.F. Bleiler, Science-Fiction: The Early Years, 783; R. Ellis and R. Williams, J.S. Fletcher, (1).

£3,500

· · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · · ·

Our Terms & Conditions apply.